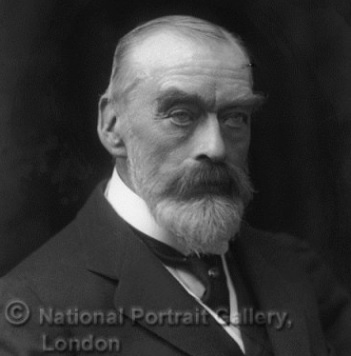

Sir Frederic Fryer, 1917

© National Portrait Gallery, London

On the 20th February, 1922, at the age of 77, Sir Frederic William Richards Fryer, first Lieutenant-Governor of Burma, died in London. He was cremated and his ashes were laid to rest alongside his wife of 50 years, Frances, in the churchyard of St. Mary’s, West Moors, Dorset.

Frederic Fryer was one of the most able servants of the British Crown in the second-half of the nineteenth century. It is unfashionable now to dwell on the role of imperial administrators of the Victorian age, but at a time in history when the United Kingdom was responsible for the affairs of nearly one-quarter of humanity and a fifth of the land surface of the globe, it was important that the civil servants sent to administer disparate lands and peoples were of the highest calibre: in my view, Frederic Fryer was such an individual and we should be proud of his stewardship and legacy.

Frederic was born in 1845, in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, the eldest son (amongst five daughters and another son) of Frederick William Fryer & Emily Frances Richards (see elsewhere on this site for a brief history of the Fryers). His early years and education are something of a mystery – mainly because the family seem to have spent several years living in Switzerland and Belgium. However at the age of 13, Frederic was enrolled at Bromsgrove Grammar School, close to his mother’s family home and the education he received there equipped him to progress to University College, London, where he was to study Law as a student attached to the Middle Temple of the Inns of Court.

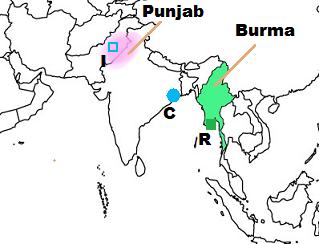

In 1863 he sat the entrance examination for the Bengal Civil Service and on being declared successful, set off for the Punjab (see map below) taking up his appointment as Assistant Commissioner and Settlement Officer in November of the following year, at the age of 19; here was a man whose talents were recognised at an early age! Only six years before, the troubles we know as the ‘Indian Mutiny’ (also ‘the Rebellion’) had engulfed the sub-continent and tension was especially high in these tribal border areas on the western flank of the Indus valley. As we will see, Frederic Fryer would prove to be an able and sympathetic administrator. Meanwhile, in August 1870, he married Frances Elizabeth Bashford in Westminster and she joined him in the Punjab: children came along, three boys being born to the couple: Frederic Arthur Bashford (known as Arthur), Francis Lyall (known as Frank) and Herbert Neville; the latter sadly died at just 9 months old & Frank was killed in action in South Africa in 1899 at the age of 26.

Outline map of the south Asia area – showing places that have particular relevance to the life of Frederic Fryer: shown are the locations of …. I: the Indus valley area; C: Calcutta (then the chief city of administration of British India); R: Rangoon (centre for administration of Burma [now Myanmar]

The Indian Mutiny demonstrated to the government in London that a more sympathetic approach to managing the varied peoples of the vast sub-continent of India was required; in particular, active attempts would be made to bring educated members of the community into management, the law and administration of infrastructure such as railways etc., and this approach seemed to suit the skills of men such as Frederic Fryer. From an appraisal of various reports on his work, it is obvious that he took a great deal of trouble to become acquainted with the local people – for example learning enough of the local language to be able to carry out negotiations on behalf of the Chief Commissioner.

This extract from the survey of land, resources and peoples of the area (written 1877) illustrates how highly he was regarded:-

(Mr J.B. Lyall, the Settlement Commissioner) “… expressed his concurrence in the Officiating Financial Commissioner’s high approval of Mr. Fryer’s labours, and remarked that he had spared no pains to acquire an intimate knowledge of the district, and had evinced sound judgement in his assessments. I think he has left a name which will be long remembered in Dera Gházi Khan. The people liked him, as he was accessible, genial, and a good linguist. His popularity and local knowledge made him a power in the district. Thanks to his discretion . . . no disturbance, conflict of authority, or other avoidable difficulty occurred in the five years during which Settlement operations were in progress.”

Then as now, nearby Afghanistan was very much a problem for Britain. In the latter years of the 1870s, British army units, together with Indian native forces were deployed in that country to prevent Russia becoming the dominant power in the region – Kipling’s ‘Great Game’. The military campaign would prove inconclusive – indeed it was marked by serious reverses for British Imperial forces. Frederic Fryer was not a soldier but he had demonstrated, after 15 years of sympathetic administration in Punjab, that he was the obvious choice to accompany the Quetta Field Force to act as a civilian liaison officer: this was a difficult and dangerous mission – then as now, the British were regarded with much suspicion, but he discharged his duty well.

The campaign in Afghanistan ended in 1880 and Frederic returned to his wife and family in the Indus valley. However, events elsewhere within ‘British India’ would draw Frederic Fryer away from the Punjab. In 1886, the Viceroy, Lord Dufferin, having initiated the forcible annexation of the nominally independent kingdom of Ava, (also known as ‘Upper Burma’) decided to unite it with the British-dominated ‘Lower Burma’, thus creating a single entity covering all of modern-day Myanmar; administration was devolved to local British commissioners residing in that country. The task would require administrators of considerable ability and finesse.

Frederic Fryer was by now renowned for his work elsewhere in Victoria’s ‘Raj’ and was an obvious choice to take up the task. In succession, he was appointed a District Commissioner (1886), Financial Commissioner (1888), then after a short return to the Punjab, he was appointed Acting Chief Commissioner of the entire province of Burma from May 1892 for two years, the most senior colonial administrator in what became known as the ‘eastern Indian Empire’, subordinate only to the Viceroy in Calcutta.

Once again he was to have a short return to the Punjab as Financial Commissioner to that important province, before settling back for the final time in Rangoon in April 1895, initially with the title of Chief Commissioner, but in 1897 it was decided that Burma, being an important (not to say strategic) part of the Empire, should have virtual control of its own administration with minimal reference to Calcutta or the India Office in London. Sir Frederic (as he was, after being invested as Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India in early 1895) became the first Lieutenant-Governor of Burma.

Overall, Sir Frederic, with his wife, spent some 17 years in Burma, and as Chief Commissioner then Lt. Governor, his term of office covered 8 of those years – the longest serving senior civil commissioner in the history of the British in Burma. Indeed, it appears that in 1899 the Viceroy, now Lord Curzon, prevailed upon Fryer to extend his service beyond the normal length such was his standing in the country & British India.

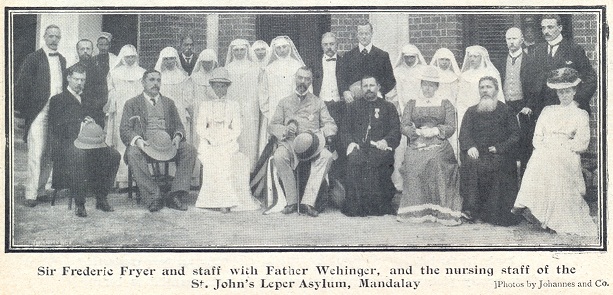

Although it was a difficult time in Burma with many problems to be faced, it appears that Sir Frederic, together with a team of able civil servants, handled the tensions between London, Calcutta and Rangoon with tact & managed to achieve a certain level of rapport with the Burmese population; for example, he was sympathetic to the Buddhist tradition in the country – supporting the case for the establishment of a Buddhist Archbishopric for Upper Burma. He also lent his weight to the gathering of funds for the foundation of a leper hospital in Mandalay – this opened in 1901. This photograph was published in the following year in the United Kingdom.

For Europeans, the humid hot climate & alien culture can be trying, but it appears that the Fryers bore the conditions with true English fortitude! However, his colonial service over, in 1903 Sir Frederic departed south Asia for the last time for retirement in London. The Fryers settled in South Kensington, not far from Imperial College and the great museums of London. Far from dropping out of public life, Sir Frederic became very active in societies that specialised in Asian affairs – contributing to papers that found their way to the governments of the day; he was also the sole author, in 1907, of Tribes on the Frontiers of Burma, a work of some note, not only at the time but it is also ‘required reading’ for modern scholars wishing to trace the history of Burma.

… And of course he was able to actively administer the lands in east Dorset that he and his wife owned.

The Fryer link with West Moors began in a tangible way in 1842 when a parcel of land along what we now call Station Road (it was just a parish-maintained trackway linking the local farms at the time) was gifted to the National School society (full name … National Society for Promoting Religious Education) by the Fryer family. These schools provided a very basic education to those children in each parish whose family could not afford to send them to fee-paying establishments. In 1843, the school opened, with a small chapel and although the original building is long gone, a sound foundation was laid for the education of many generations of West Moors children by this action.

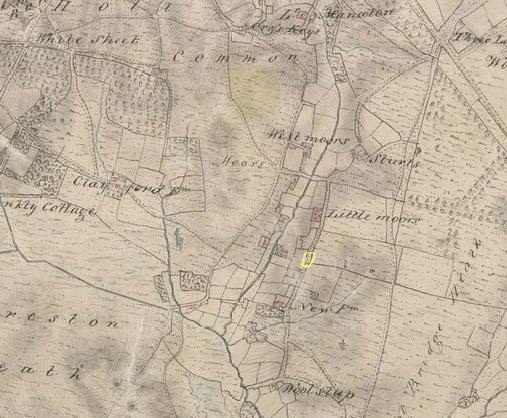

[ The map below is a copy of the early Ordnance Survey edition of the early part of the 19th century (pre-railway): the first school in West Moors would have been somewhere within the area marked in yellow. ]

By the mid-1890s, the village was growing, albeit in a rather haphazard manner. The population of the area approximating to modern-day West Moors was around 150-250 (depending upon how the area is defined) with circa 45-50 scattered dwellings. It was clear that a separate place of worship and a larger school were required. To facilitate this, Sir Frederic & Lady Fryer conveyed a piece of land along Station Road for the sum of £37 10s (£37.50) or roughly £2000=at modern prices. On this site was built the present-day church and a school, together with a house for the schoolmaster & residence for a curate. All these buildings were funded solely by Claud Brown, who was Vicar of Verwood (that parish included West Moors): a truly magnificent gift. To read more on this, follow this link.

Both the school and church have been extended – the latter quite recently; the school house & curacy (later the vicarage) are now in private ownership. However, these buildings can be seen today and are notable examples of late Victorian architecture. Finally, in 1914, the family offered land opposite the church and school for the erection of a village hall & provision of playing fields. The Great War prevented any progress on this project, but after the war, funds were raised by public appeal and the Memorial Hall was erected on this plot of land, opening in 1929. Neither his wife, who died on Christmas Day 1920, nor Sir Frederic lived to see the Hall brought into use.

As far as I can determine, at no time did either Sir Frederic or his father Frederick William Fryer, actually live within the parish of West Parley, let alone the small hamlet of West Moors, yet through considerable landholdings inherited from Frederick William’s grandfather, the ‘reformed’ smuggler Isaac Gulliver, the Fryer family had always regarded this small community as their ‘home’. Sir Frederic & Lady Frances, along with their son, Frederic Arthur and four of their five grandchildren, have a final resting place in a quiet corner of the churchyard of St. Mary’s, here in West Moors – not far from the playing field that carries their family name.

I am grateful to the staff of Bromsgrove Grammar School for information on Sir Frederic’s years there and I also acknowledge the considerable help and encouragement from Andrew Rowland, vicar of West Moors (at the time of writing this article). The image of Sir Frederic in 1917 at the head of this page was sourced from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery and I thank them for their help.

Martin Rowley, West Moors, Dorset.

December 2011

Sources: (not all of these may be active)

http://www.stmaryswestmoors.org.uk/parish_history.htm [ last accessed 14th December 2011: this latter a particularly useful source ]

http://www.archive.org/stream/burmaunderbritis01nisb/burmaunderbritis01nisb_djvu.txt

[ last accessed 14th December 2011 ]

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Indian_Biographical_Dictionary.djvu/191 [ last accessed 14th December 2011 ]

http://search.fibis.org/frontis/bin/simplesearchsummarycat.php?mode=q&FrontisKeyword=Fryer&FormsButton1=Go&s=1

[ last accessed 14th December 2011 ]

http://tinyurl.com/3stdvzj [ last accessed 14th December 2011 ]

http://tinyurl.com/4xd4quw [ last accessed 14th December 2011 ]

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a/records.aspx?cat=059-lpj6_623-711&cid=-1#-1

[ last accessed 14th December 2011 ]

http://www.archive.org/stream/finalreportonfi00fryegoog#page/n41/mode/1up [ last accessed 14th December 2011 ]

” Governing British Burma: The career of Charles Bayne (1860 – 1947) in the Indian Civil Service ” author: Nicholas Bayne; London School of Economics and Political Science, UK.